Does ice in the universe contain the building blocks of Life?

JWST allows astronomers to ask whether ice in the universe contains the molecules making up the building blocks of Life in planetary systems

The James Webb Space Telescope – the most precise telescope ever built – was decisive in discovering the frozen forms of a long series of molecules, such as carbon dioxide, ammonia, methane, methanol and even more complex molecules, frozen out as ices on the surface of small dust grains.

The dust grains grow in size when being a part of the discs of gas and dust forming around young stars. This means that the researchers could study many of the molecules going into the forming of new exoplanets.

Researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, combined the discoveries from JWST with data from Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), making observations in other wavelengths than JWST, and researchers from Aarhus University contributed to the necessary investigations in the laboratory.

Lars Kristensen, associate professor at the Niels Bohr Institute (NBI), explained: “With the application of observations, e.g. from ALMA, it is possible for us to directly observe the dust grains themselves, and it is also possible to see the same molecules as in the gas observed in the ice.”

Jes Jørgensen, a professor at NBI, added: “Using the combined data set gives us a unique insight into the complex interactions between gas, ice and dust in areas where stars and planets form.

“This way we can map the location of the molecules in the area both before and after they have been frozen out onto the dust grains and we can follow their path from the cold molecular cloud to the emerging planetary systems around young stars.”

targeted ices

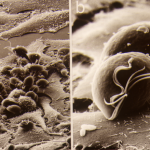

The ices were detected and measured by studying how starlight from beyond the molecular cloud was absorbed by icy molecules at specific infrared wavelengths visible to Webb.

This process leaves behind chemical fingerprints known as absorption spectra, which can be compared with laboratory data to identify which ices are present in the molecular cloud.

In this study, the team targeted ices buried in a particularly cold, dense, and difficult to investigate region of the Chamaeleon I molecular cloud, a region approximately 600 light-years from Earth which is currently in the process of forming dozens of young stars.

Along with star-forming comes planet-forming and the perspective for the researchers in the IceAge collaboration is basically to identify the role the ice plays in gathering the molecules necessary to form Life.

Sergio Ioppolo, associate professor at Aarhus University, who contributed to some of the experiments in the lab that were compared with the observations, explained: “This study confirms that interstellar grains of dust are catalysts for the forming of complex molecules in the very diffuse gas in these clouds, something we see in the lab as well.”

Klaus Pontoppidan, a JWST project scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, USA, who was involved in this research, said: “We simply couldn’t have observed these ices without Webb.

“The ices show up as dips against a continuum of background starlight.

“In regions that are this cold and dense, much of the light from the background star is blocked and Webb’s exquisite sensitivity was necessary to detect the starlight and therefore identify the ices in the molecular cloud.”

The IceAge team has already planned more observations with both Webb and other telescopes.

Image: A large, dark cloud is contained within the frame. In its top half, it is textured like smoke and has wispy gaps, while at the bottom and at the sides it fades gradually out of view. On the left are several orange stars: three each with six large spikes, and one behind the cloud which colours it pale blue and orange. Many tiny stars are visible, and the background is black. Two stars are denoted with white text. © NASA/ ESA/ CSA/ and M Zamani (ESA/ Webb)/ F Sun (Steward Observatory)/ Z Smith (Open University)/ IceAge ERS Team.