Six years on from the UK’s historic referendum vote to leave the European Union, there is still no clear route forward for the country’s scientists and their continued participation in the Commission’s Horizon Europe research programme.

Scientists are by definition the most exacting of people; to have gone through so much uncertainty over so many years is the worst of all worlds. Aether investigates the effect this situation is having on the UK’s researchers and scientific institutions.

When the British public voted to leave the European Union on 23 June 2016 many sectors immediately raised their concerns for the future, but perhaps none more so than the scientific community.

The European Commission’s framework programmes, dating back to 1984 and, at the time of the 2016 referendum, in its eighth iteration as Horizon 2020, was the key source of funding for the vast majority of scientists across Europe. The UK’s scientists and scientific institutions immediately realised the potential repercussions of the ‘Brexit’ vote and, six years on, confusion still reigns as the UK Government and the European Commission have yet to find a compromise solution that gives a clear path on the participation or otherwise of UK researchers going forward.

The reason for this continued uncertainty can largely be put down to that part of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, ratified in January 2020, and known as the Northern Ireland Protocol. The largely invisible land border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland was made possible as a result of the Good Friday Agreement of 1997, but Brexit made the border on the island of Ireland the only land border between the European Union and the UK. The protocol was designed to prevent a return to a ‘hard border’ and the potential threat to the peace it accorded, by recognising Northern Ireland as formally outside the EU single market, but that EU free movement of goods rules and EU Customs Union rules still applied. In effect the border was placed in the Irish Sea, between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, causing great resentment amongst loyalists in Northern Ireland, and an accompanying threat to peace.

The protocol was part of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), in which the UK negotiated access to a range of EU science and innovation programmes, notably Horizon Europe and Copernicus, the Earth observation programme, which provides data on climate change, as well as Euratom, the nuclear research programme, and access to programme services including Space Surveillance and Tracking.

The EU has yet to finalise UK access to these programmes which, according to London, has caused ‘serious damage to research and development in both the UK and EU member states’.

Outrage

The reasons are many, but perhaps the clearest and certainly most recent occurred in June 2022 when the UK Government under Prime Minister Boris Johnson, sought to implement a new Northern Ireland Protocol Bill that, if enacted, would unilaterally remove some aspects of the original protocol.

It caused outrage in Brussels. EU Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič warned of repercussions and, specifically, highlighted the UK’s continued involvement in the flagship Horizon Europe research programme as one area where the Commission could potentially target the UK. British institutions were immediately faced with the very real prospect of losing access to billions of euros of research funding with scientists being cast out of consortia they had been a part of for many years.

However, by the middle of July, Boris Johnson had been forced to resign as leader of the Conservative Party and said he would step down as the country’s prime minister when a successor was elected. Suddenly the future for the country’s scientists looked brighter as Johnson and his administration were seen in Europe as the cause of the ongoing uncertainty. Instead of statements threatening the UK’s continued involvement in the Horizon Europe programme, the Commission and other leading Europhiles breathed something of a sigh of relief, believing the next UK administration would be more willing to compromise on Brexit.

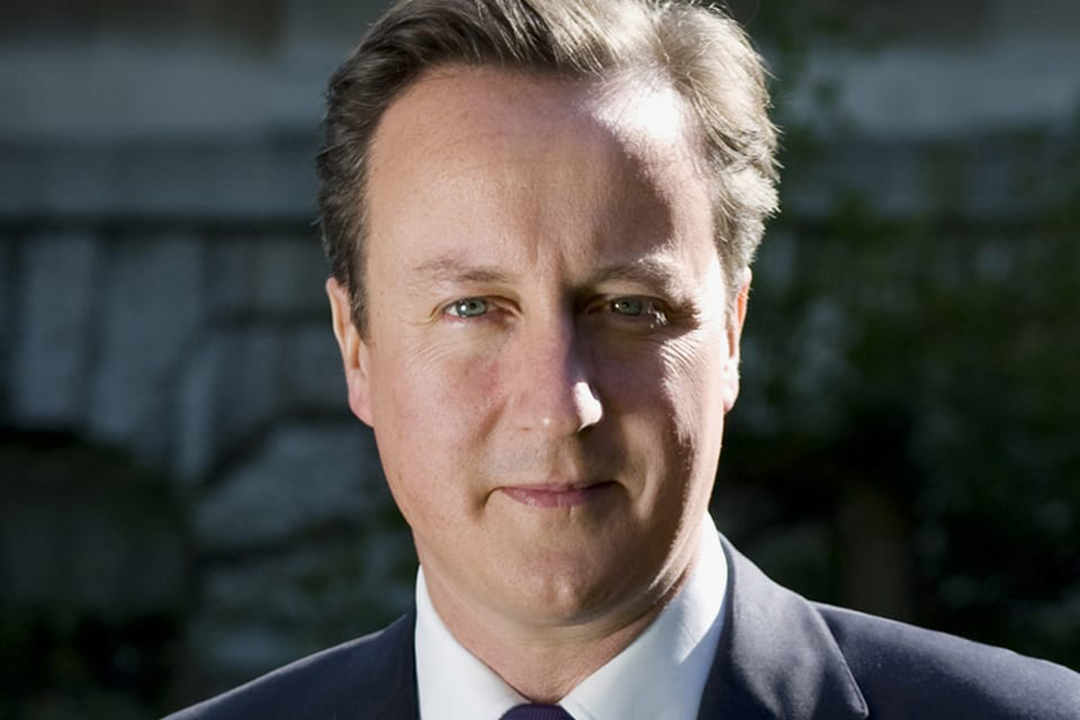

It is more than six years since the Brexit referendum instigated by former prime minister David Cameron.

The collapse of the Johnson government in July gave renewed hope of softer negotiations on Horizon Europe

With a new prime minister yet to be decided, the uncertainty over Horizon Europe has now entered a new and somewhat surreal phase; it is positive in the recognition that the stumbling blocks caused by the Johnson administration are no longer there, but there is no real idea of the approach of the next UK government. The situation facing researchers across the UK can still be summed up using one word; they are in limbo.

The end of a prime minister

But is there now light? One aspect of the current situation that has worried UK researchers almost as much as their potential non-participation in Horizon Europe has been the lack of a recognisable ‘Plan B’. Rumours swirled that the government had to have something in reserve should negotiations go so badly that they were no longer welcome in European-funded programmes.

The minister of science for almost a year had been George Freeman, but he was one of 62 Conservative MPs to resign their posts during the UK government crisis of early July that led to the collapse of the Johnson administration. Frustratingly, and once the dust had settled whereby the existing administration would form a caretaker government while a new Conservative Party leader was elected, it became clear that there was no longer a UK minister for science. Freeman’s role was not reprised.

Despite there being a government in place, and one which stated it would not enact any major policies until the new prime minister was elected, the resolution of the UK science funding question seemed ever further down the political agenda. Not only that, but there also seemed to be no one to appeal to on the issue, no one who was able to stand up in front of the scientific community and say there was a plan in place should subsequent negotiations fail.

Then it all changed. Again. On 20 July, the UK Government published a new framework, with little fanfare and even less media coverage. The one thing scientists had been crying out for had finally arrived; the government’s fallback position. Titled ‘Supporting UK R&D and collaborative research beyond European programmes – how the UK will transition to a new R&D programme if unable to associate to Horizon Europe, Copernicus and Euratom’, the paper gave the first clear insight into how the country’s scientists, research institutes and businesses would be helped going forwards.

And it was far reaching. The new package of transitional measures was geared to ensure the stability and continuity of funding for researchers and businesses, which would come into force if the UK was unable to associate to Horizon Europe.

The stalemate of recent months went undimmed, but the UK Government was keen to emphasise its wish to remain in the EU funding programmes given the agreement made in December 2020 to associate to Horizon, Copernicus, Euratom Research & Training, and Fusion for Energy as part of the TCA made between the EU and UK. The government statement was quick to point out the advantages of working together in an association that would benefit all parties, enabling countries across Europe to work together on shared challenges.

But to the bemusement of some in Brussels, the paper also argued that in light of the EU’s continued delays, the UK made clear that should association not be completed, its priority was to protect and support the research and innovation sector, with the funding allocated for association being re-directed to new R&D programmes, including those designed to support international partnerships.

Plan B, therefore, was a desire to set up an equivalent programme and, perhaps one that might work in competition with the EU’s own funding streams. Was the UK looking to create a new funding stream to go it alone in world research, or is the plan to simply ensure there is no funding gap for the R&D sector, providing immediate funding opportunities for researchers, institutions, and businesses while longer-term measures are established?

Ready to launch?

The transitional measures outlined in the paper specifically highlighted seven areas of immediate concern: the UK Guarantee scheme already in operation; funding for successful, in-flight UK-based applicants to Horizon; uplifts to existing UK talent schemes; uplifts to innovation funding and support for businesses, in particular SMEs; uplifts to international innovation schemes to support international business collaborations; funding for research institutions most affected by the loss of Horizon Europe’s talent funding; and continued third country participation in Horizon Europe.

It is clear from the language used that the UK Government is confident the measures will be delivered by trusted and experienced UK bodies, using existing and well-established UK funding and support mechanisms, and will be ready to launch if the UK is unable to associate to Horizon Europe.

The long-term programme, the paper stated, is to be established as quickly as possible, and the government said it was already in conversation with researchers and businesses to determine priorities for a programme that would help build on UK strengths and develop new capabilities, while distributing resource and support for the sector right across the country, in line with the Johnson administration’s now well-known agenda of ‘levelling up’ across the UK regions, investing in those parts that perhaps see less attention than the geo-economic powerhouse that is the southeast of England.

Lastly, the paper stated the government was also developing a comprehensive plan of alternatives to Euratom R&T, Fusion for Energy, and Copernicus programmes, including other interim measures.

So, what are those longer-term measures and what do they entail? Are we now seeing the UK hit back with a threat to EU-funding programmes far into the future, or is London simply looking after UK science as the uncertainty continues? The rhetoric could be considered both of those things. In reaction to the issue of scientific funding being used as a political bargaining chip by Brussels, and, tellingly, publicly so, so one of the last acts of the outgoing Johnson administration has been to place firmly the ball back in Europe’s hands. For instance, the paper set out a preliminary vision for a long-term, alternative programme to Horizon should it be required, which will focus on four main themes to complement existing R&D investments: talent; end-to-end innovation; global collaboration; and investments in the R&D system.

Clear breach

Then a curveball; on 17 August, the UK Government issued another challenge to the EU in opening ‘formal consultations’, a mechanism set out in the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement to resolve disputes between the UK and EU. London called for an effort to ‘end persistent delays to the UK’s access to EU scientific research programmes, including Horizon Europe’.

The key individual behind the call was Foreign Secretary Liz Truss who is locked in a battle with former chancellor Rishi Sunak to become the UK’s next prime minister. Truss, it has to be said, is probably not Europe’s choice for the next UK prime minister; she stayed loyal to Boris Johnson and, therefore, remained as Foreign Secretary, which is why her name was at the top of the formal consultation call. She is also seeking to carve a reputation as a tough talking politician in the mould of Margaret Thatcher, even to the point of wearing an outfit almost identical to the Iron Lady in one of the earlier national TV debates to decide who would become the next prime minister.

She was bullish in her comments: “The EU is in clear breach of our agreement, repeatedly seeking to politicise vital scientific co-operation by refusing to finalise access to these important programmes. We cannot allow this to continue. That is why the UK has now launched formal consultations and will do everything necessary to protect the scientific community.”

Minister for Europe Graham Stuart added: “It is disappointing that the EU has not facilitated UK participation in the agreed scientific programmes, despite extensive UK engagement on the issue. Now, more than ever, the UK and the EU should be working together to tackle our shared challenges from net zero to global health and energy security. We look forward to constructive engagement through the formal consultations.”

EU Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič has warned the UK may lose its access to Horizon Europe over its stance on the Northern Ireland Protocol

Favourite to succeed Boris Johnson as UK prime minister, Liz Truss has already warned the EU of the failures of finding a solution on the UK’s Horizon Europe participation.

The letter argued that UK membership of Horizon Europe would be a win-win for both the UK and EU, because the UK is a world leader in science and technology, houses some of the most research-intensive universities in the world and led the global effort to combat COVID-19. The statement also said around £15 billion had been set aside for Horizon Europe alone.

It was a remarkable development; a caretaker government castigating the EU over what were described as European Commission attempts to ‘politicise scientific co-operation’. What is more, it is a caretaker government that promised no new major policy announcements. But Truss is favourite to win the leadership race and become the next Prime Minister of the UK. So, is the decision to face up to the EU coming from a super confident politician reaching her zenith?

Will the EU succumb to the demands and allow UK access to Horizon Europe and the other programmes? Or has, as some are already suggesting, Truss gambled on the EU refusing to meet her demands thus paving the way for the implementation of ‘Plan B’?

The EU, and Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič in particular, may have highlighted the UK’s decision to potentially unilaterally disregard the Northern Ireland Protocol as the reason for the delays, but the announcement of 17 August makes that stance seem somewhat redundant. The uncertainty remains, but has the UK broken the deadlock one way or the other? It seems the ball is very much in the EU’s court.