A key focus that has come out of the European Commission recently is the need for greater transparency in the research programmes it funds. ‘Exploitation’ is the term used and it is basically designed to ensure that the research EU funding pays for is made more available to the taxpayers that funded it.

Profile: Claus Hessler Ibsen is Group R&D Director at Vestas aircoil A/S; a Danish manufacturer of charge air coolers, intercoolers and cooling towers in existence since 1956.

It is a moot point whether that has a detrimental effect on blue sky research, but it should hone the eye of the researcher looking to access funds for their projects. There are opinions on all sides of the argument, but for Claus Ibsen, it is a welcome development.

Here he gives his thoughts to Aether on the need for academic research to be more closely aligned with industrial deployment.

How do you personally define the gap between industry and science?

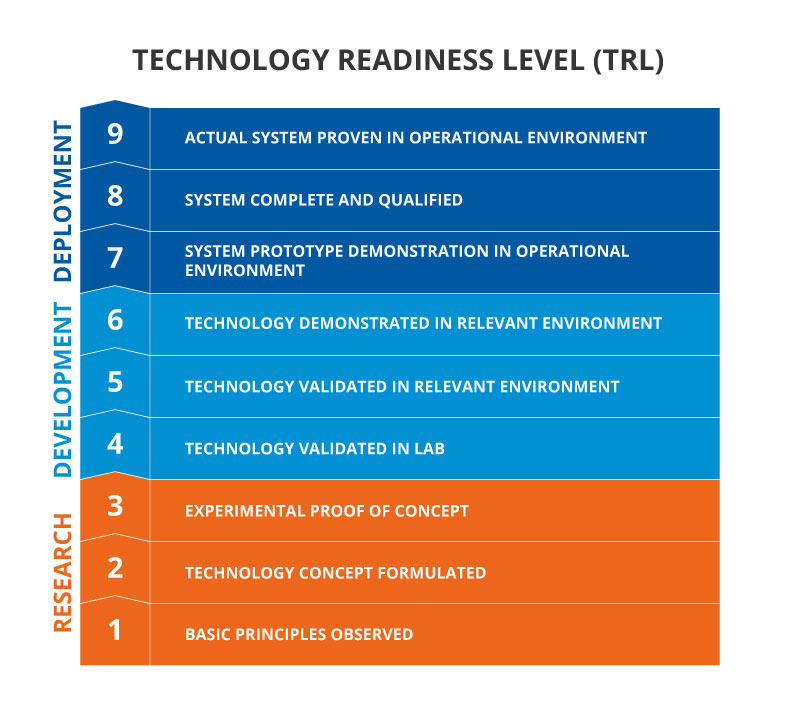

The European Union uses a technology readiness ladder to decide where on that platform a project or technology is. It was originally developed by NASA in the 1970s and recently we have started using it. It’s a very well-known graphic and you use it to assess where you start and where you expect to end up with regards to the technology, or whatever it is you are developing, and how ready it is for market. It’s a good way to see where you are with a research project, and it provides a good starting point for discussion.

The academics are typically in the bottom three rungs of the ladder, the orange area, and industry, with their market-ready projects, are somewhere in the top three dark blue rungs. The challenge is the light blue area in between. That area represents a vast gap in man-years between academia and industry, and it is that which we must tackle.

An academic might come to me with an idea having done their PhD. I might find their new thesis interesting, I might see the potential, and it might clearly be in tier three, the top tier in the orange section. It then might take another ten years for me to actually have something to work with within industry. And in terms of man-years that could be close to £1m, so that is quite a heavy investment, both in terms of time and cost, to get that project into deployment.

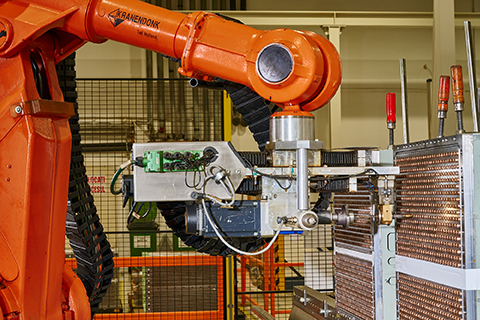

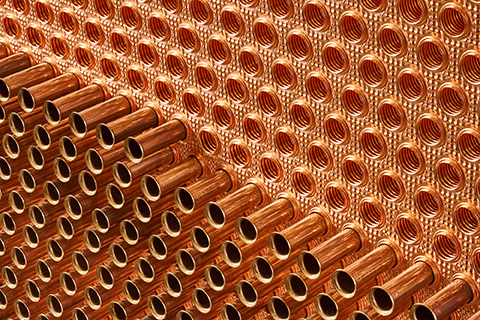

With our projects, we aim to make it into deployment much more quickly, but that is not necessarily easy. The coolers we are producing are large. They need to be more structurally solid than you would see on a normal car because they are used on some very large engines. But we have to adapt structurally in a smart way, not just by adding more material. There are temperature gradients in the coolers which provide localised stresses which can be the starting point of a crack, and this is an example of the gap between research and deployment.

We have a PhD student with us who is working on an interesting project to check for cracks in materials using additive manufacturing (3D printing). The specimens he was using might be 100mm long and 10mm by 10mm in cross-section, so very small samples. He can test these materials, see how much stress it can maintain or see how many cycles it can be put through before you start to see localised failing.

This is very interesting, but it is limited. The largest 3D metal printers are somewhere in the region of 300mm x 300mm whereas our coolers can be three metres long and two metres wide. The samples we get from 3D metal printing are far too small and although the information we are getting is interesting, it is not mature enough for us to start using it.

What would you like to see happen to narrow the gap between the research and deployment stages? Do you think it is possible to shorten the development stage?

Yes, I think it is possible. Industrial PhDs here in Denmark find the challenges that are more closely related to the actual product the companies are looking for.

It is all in the scoping; if you are a researcher and you want to get a PhD, aim a little higher and write your articles for scientific journals. But you are only going to succeed if your articles continue to carry a ‘news’ value for the journal. One could argue it is easier to generate news value if you look into something which has never been investigated before, but that will be very low on the TLR ladder.

Or maybe you want to go into a well-known area where you will need to drill right down to get any news value out of it. To get there sooner, as a researcher, do much more scoping around your subject and maybe you can shorten the development stage. Likewise, companies can outline what they need or are looking for, and that would help the researcher to consider their ideas and ultimately how long they spend researching a particular area.

To what extent do you think it’s the role of industry or science or even government to try to shorten this process and make it easier to turn research into deployment?

I would say it is everybody’s responsibility to improve it. At the university level, I see a difference in the approach to industrial PhDs from different countries. For example, an idea might come out of the UK where the approach to industrial PhDs is different to that found in Denmark. But I think it would be very interesting to collaborate and see whether we can learn from each other in terms of that project.

For me, I would like to think I am bringing the scoping aspect to a particular project and if it was something others became aware of and it was taken on board, then yes, we might see a shortening of the overall process. There are also things I am sure researchers from other countries could show me as well.

Is the system set up in such a way that it is actually working against getting things deployed sooner?

It is a little bit too cautious. Obviously, if we are looking at a dangerous system then we need to have the right level of caution, but for me, often the thesis will not be right because it is purely academic. It might be interesting to read, but it has no value for a company. I cannot make use of it.

There’s an onus on the scientist to explain their research better. And again, some researchers spend a lot of time working on the toy problems when perhaps they should really be looking to use the tools or methods that develop from actual case studies.

If you do not scope a project correctly, then it is difficult to get away from the toy problem. It will then, once again, just be an academic exercise, which doesn’t really have much interest in it for the industry and the companies. If you scope the project correctly, you can make the whole thesis much more interesting for both academia and industry.

Therefore, going forward you would like to see something of a working prototype be an integral part of a proposal for research?

When we are involved in funded projects, we are not necessarily doing it to have a final product developed. It is more about developing models where you can say you have a new tool in your toolbox that you can use for developing your product. It is the ‘toolbox’ of models or software codes that I want to expand. That should mean a researcher or research group is able to scope their project to make these tools that can easily be adopted into my research and development of coolers, for instance, and I am certain that can be done.

We have something a little like this here. A new colleague of mine is a former university professor and his latest PhD student (who is not affiliated with our company) was researching the evaluation of material properties by hydraulic expanding of tubes with very high pressure. Eventually, the tube will burst when the pressure reaches a peak value. He defended his thesis this spring just gone, and we have actually started using this method of evaluation ourselves in our R&D Lab looking at tubes from different suppliers. Six months on from handing in his thesis and we are using it. That is how it should be.

Do you therefore welcome the EU’s new focus on the ‘exploitation’ of research?

Absolutely. If funding comes from the EU with the intention of creating new methods or new products, then yes, you need to be able to explore and show that the research you have undertaken can be used.

Do you think there’s an ethical responsibility on the part of scientists and industry leaders to make their advances more publicly known to the benefit of the whole of the EU?

Following on from the last question, we need to ensure that the research EU funding pays for is made more available to the taxpayers that funded it. That is an essential.

But we also need to move away from ‘scientists’ and, particularly, ‘industry’ and their concept of intellectual property rights. Industry should be less worried about keeping that to themselves and instead they should look to get it out there more.

Going back to the idea of tools; being part of a funded project is about developing some tools, which I will then use to improve my products. I don’t mind sharing the models with other companies because it is how I use the models afterwards, which is where we differentiate from other companies. I don’t necessarily have an issue sharing these models with other companies.

Maybe the focus should be more on model development and not necessarily on the end product? It is the journey you are on which is interesting, not necessarily the end goal.

Claus Hessler Ibsen / Vestas aircoil A/S / www.vestas-aircoil.com